India’s historic and vernacular architectures are rich in cultural influences — in fact, they are born out of the cultural identities of the communities that occupy them. However, buildings today often follow a homogenized set of aspirations — a building in Delhi looks no different from one in Tokyo or New York. Sharon Sabu, Architectural Design Manager at Epistle Communications, explores whether the expression of cultural identity in architecture is important, and why this expression can be instrumental in finding a contemporary language of Indian architecture that is sustainable and truly ours.

Also Read: 7 Simple steps to Declutter your Work Space

In an Aga Khan Award for Architecture seminar in 1983, celebrated Indian architect Charles Correa defined cultural identity as “the trail left by civilization as it moves through history.” The identity of belonging to a social group with common characteristics, cultural identity includes elements like religion, language, culinary practices, and dressing habits, which accrue and evolve as they are passed down through generations.

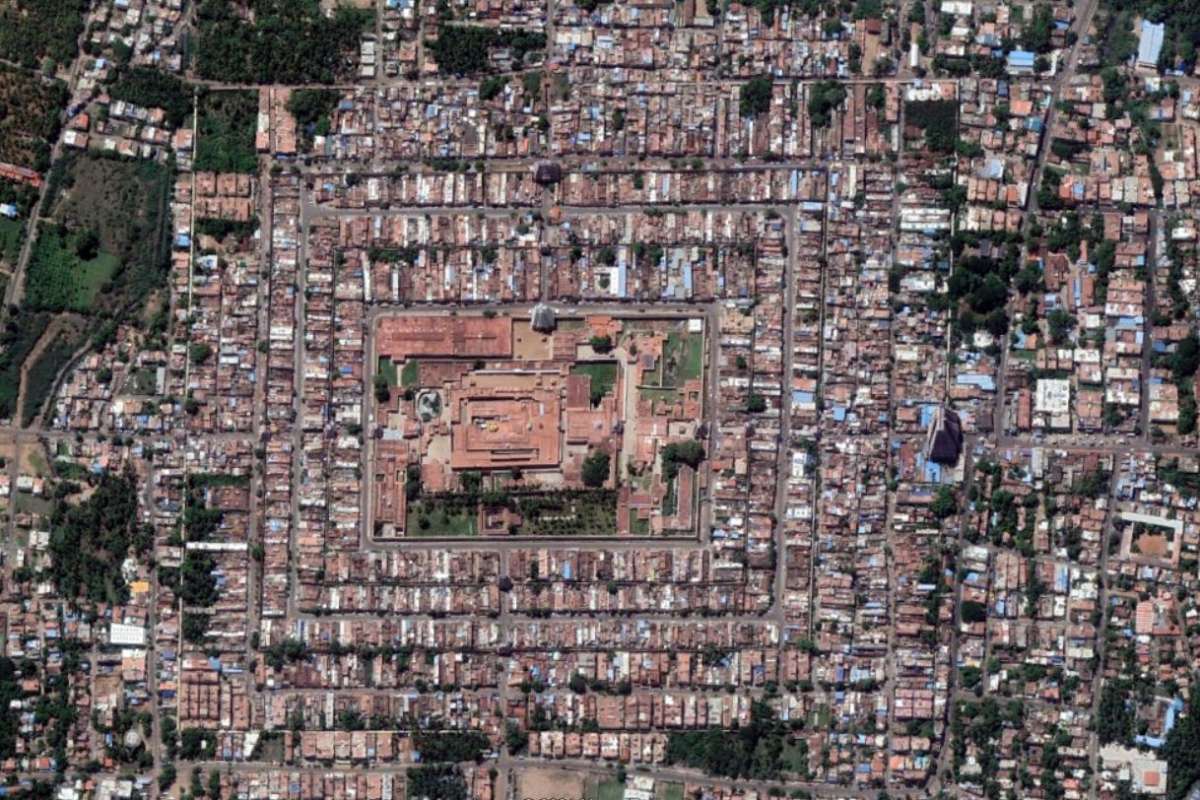

Historically, architecture in India has served as a tangible expression of cultural identity, providing vital clues to later generations about what constituted a region’s culture during a particular period of time, what was important to its people and communities, and how they chose to depict it. The way traditional Indian buildings and cities are designed or planned speaks volumes about the cultural traditions and societal structures of the communities that inhabited them.

Also Read | Shiro Kuramata’s Samba-M shines again with Ambientec at the supersalone in Milan

However, Indian architecture today is a far cry from the culturally-expressive built environments of the past. “A lot of our traditional cultural identity is being lost due to globalisation and changing aspirations,” says Gaurav Shorey, energy consultant and founder of 5waraj, a Delhi-based NGO dedicated to reviving faith in regional cultural wisdom. “Today, we eat food, wear clothes, and live in homes that are borrowed from cultures from vastly different contexts — cultures that are not appropriate to our regional context. This transition has disconnected our lives and buildings from their natural settings.”

What Shorey says can be easily observed in most Indian cities today, with concrete and glass-sheathed towers increasingly replacing their diverse and contextually-derived architectural landscapes. However, in this age of blurred socio-cultural identities, is the expression of cultural identity still important to contemporary Indian architecture, and if so, why?

Experts like Shorey have observed that indigenous cultures and identities almost always emerge from a response to nature and climate. “Culture is not a fixed, old-versus-new phenomenon,” he says. “It is a logical reaction to local, geo-climatic conditions, as valid and in practice today as it was millennia ago.”

Shorey identifies five distinct elements of Indian culture that have emerged from this, elements that are part of an interconnected, holistic system — bhaashaa (dialect), bhojan (diet), bhesh (dress), bhavan (dwelling), and bhajan (dance and music). “All of these elements have emerged from local climates and have done so within the limits that nature has to offer at a local level. Any architectural expression born out of such a cultural identity is, as a corollary, inherently sustainable,” he says.

Also Read | 7 decor must haves for your living room

The direct link between climate and culture can be observed through many examples: the spicy food of Andhra Pradesh that induces a cooling effect, the cotton lungis of Kerala that enable evaporative cooling, or the multi-faceted façade of the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur that reduces heat absorption through self-shading. An intrinsic consciousness about climate and consumption patterns is at the heart of Indian culture — an awareness that is critically important in the light of climate change and needs to be integrated into our built environment, now more than ever.

The architecture of post-Independence India includes some glowing examples of the integration of traditional cultural wisdom into the built environment, blended with the technology and material advancements of the modern era. Conceived by Correa in 1982, the design of the Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal is inspired from the sunken courtyards of the 16th-century Agra Fort, resulting in a subterranean campus of enclosed spaces and open-to-sky courts.

Also Read | GROHE’s retrofit line bets on convenience and experience

Located below ground level, the open spaces are protected from Bhopal’s scorching heat and provide naturally-cooled communal spaces for its users. Similarly, the Asian Games Village in Delhi, designed by Raj Rewal in the same year, was inspired by the dense urban fabric of the desert city of Jaisalmer, which is characterised by closely-spaced residential clusters and self-shaded pedestrian paths.

Today, many promising architects across the country are also designing sustainable buildings inspired by traditional design principles. The Gadi House in Talegaon Dabhade, Pune, designed by PMA madhushala, is evocative of the regional gadi (fortress) house forms and covered with a thick outer skin for thermal protection. Small openings punctured in this skin cool the air as it flows in, drawing on Bernoulli’s principle and the Venturi effect, which govern the working of traditional jaali screens. Inside, a combination of courtyards and semi-open terraces — both distinct features of the wada, the traditional residential forms of Maratha architecture — facilitate natural ventilation within each part of the house.

Also Read | 6 interior design trends for winter season

While PMA madhushala often draws from elements of traditional residences, Noida-based Studio Archohm borrowed from the monumental architecture of Lucknow for the design of Awadh Shilpgram, a crafts bazaar that opened in the city in 2016. Designed as a facility for tourists and local craftspeople, the Shilpgram’s elliptical market building is ringed by an arched corridor that is reminiscent of two of the best examples of Awadhi architecture, the 18th-century Bara Imambara and Roomi Darwaza. The corridor provides a shaded walkway to pedestrians, serving as a comfortable transition between the market street and the shops. The winding market street is also a direct nod to the narrow streets of Lucknow where adjacent buildings shade pedestrian paths from direct sunlight.

Expressing cultural identity through contemporary architecture can also play a crucial role in revitalising cultural ecosystems. Craft, one of the most tangible expressions of culture, is found in differing forms and mediums across the country, with many of these practices at risk of being forgotten today with decreasing patronage and platforms for development. “Each region within our country has much to offer by way of vernacular built vocabulary, and more importantly, prevalent local skills and material usage. The co-creation of a design narrative using local crafts offers a great opportunity to craftsmen to give their skills and traditions a new life,” says Ankur Choksi, Principal at Studio Lotus, a Delhi-based multidisciplinary design practice. The inclusive approach adopted by the practice incorporates artisans and craftspeople into the design process, allowing their expertise and input to shape the final product.

Also Read | Ameliorate your interiors this festive season with these seasoned recommendations

Completed in 2010, the RAAS hotel in Jodhpur, Rajasthan was an experiment in this approach. Conceived by the studio in collaboration with Praxis, the project provided livelihoods to over a hundred regional artisans and master craftspeople. An extensive process of prototyping and artistic explorations resulted in contemporised expressions of craft in sandstone for the building, like its sliding jaali screens. RAAS Jodhpur was nominated for the prestigious Aga Khan Award for Architecture and is one of the most popular luxury properties in the city, its widespread acclaim giving a fillip to the craft economies of the region.

Several non-governmental organisations and private agencies are also working at the intersection of craft and architecture today, creating a place for indigenous artisanship in contemporary architecture. The Gujarat-based Hunnarshala Foundation’s Sankalan Artisan Empowerment Programme helps develop sustainable building crafts into viable business models by providing formal training to craft communities and assisting them with legal procedures and financial support.

Some of the initiatives fostered under the programme include Layers, a company specialising in rammed earth construction, and Matha Chhaj, a women’s collective specialising in the installation of thatched roofs. These artisan-led initiatives were recently employed at Jetavan, a Buddhist spiritual centre in Maharashtra designed by Sameep Padora & Associates, where Layers created its rammed earth load-bearing walls and Matha Chhaj developed the roof’s under-structure from mud rolls.

Expressing cultural identity in our built environments isn’t just important to facilitate environmental and socio-economic sustainability, but also as a reminder of the values and ideals that define us as part of a community. When architecture reflects the cultural values we identify with, it implicitly reminds us of who we are and reinforces our human psyche, enveloping us in a comforting layer of familiarity. In doing this, architecture transcends tectonic concerns and touches the human spirit, and an inanimate form like a building is imbued with life.

Also Read | Ethically crafted home decor for the modern Indian home

However, owing to the diversity of cultures in our country, these expressions must not be limited to a few motifs or materials used nation-wide. They must instead emerge from the distinct climatic considerations and cultural histories of their individual contexts, reflecting the spirit of their place.

This article has been published in an editorial partnership with Epistle Communications.