Kushagra Sharma, Senior Design Manager, Epistle Communications, probes if we can resolve some of the challenges our cities face today by bringing empathy into the design process.

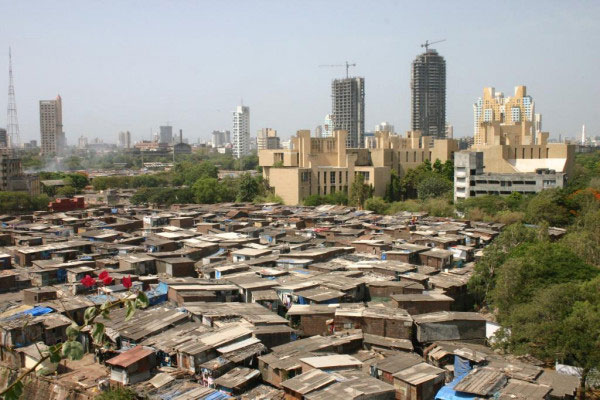

Cities have continued to thrive for millennia as economic engines and hubs of innovation and culture, holding the promise of a better quality of life for many. Today, however, urban centres across the globe are grappling with a multitude of crises; Delhi’s air pollution, Mumbai’s poor civic infrastructure and shortage of housing, and Bengaluru’s traffic woes and toxic lakes are just a few glaring examples.

Also Read | The design of this Pune school seamlessly includes fun, joy, and play into learning

Many architects and urban planners believe that one of the root causes of the many challenges we face today is a lack of empathy in the way we consume resources, how our cities are designed and function, and whom they are designed for. With India projected to add a staggering 416 million urban dwellers by 2050, what does our urban future look like?

“The predisposition to design environments that exclude certain segments of society and neglect environmental concerns is part of a larger problem and the easiest-to-understand implication of that is climate change,” states veteran architect M.N. Ashish Ganju. For instance, unabated construction in Chennai, sometimes encroaching into its wetlands, and apathy towards protecting and replenishing its water resources resulted in the city facing a major water crisis in 2019.

In Bengaluru, environmental pollution has reached a peak today with its water bodies choking with toxic waste. According to a study conducted by the Environmental Management & Policy Research Institute (EMPRI), discharge of untreated sewage and industrial effluents have rendered the water in every single lake in the city unfit for drinking and bathing. Bellandur and Varthur Lakes, Bengaluru’s largest water bodies, have even been reported to spew up to ten-foot-high toxic foam onto adjoining streets. Ganju believes that design is a major contributing factor that has brought our cities to this tipping point. “Empathy was not a driving characteristic of design — it just wasn’t a priority,” he says.

In transport planning too, how people move through and experience the city has for long been neglected. Most Indian cities are not designed for pedestrians — who in urban centres constitute the vast majority of the population — an approach that has led to a sharp spike in accidents in the last few years. Pedestrian fatalities across the country have risen by 84% between 2014 and 2018 as roads continue to encroach upon pavements, leaving citizens at the mercy of motorized traffic.

This lack of empathy also manifests in how governments have addressed the issue of housing the urban poor. Mumbai, for instance, has for decades struggled to ensure a dignified way of living for its ever-increasing migrant population. With its geographical limitations continuing to drive up real estate prices, most inhabitants are forced to settle in squatter settlements and multi-storey tenements with abysmal living conditions. “If one looks at the chronological framework of government policies implemented to alleviate the plight of people living in slums, a model of clearing the ‘encroachments’ and rehousing slum dwellers in subsidised rental housing can be observed,” says Rahul Kadri, Partner and Principal Architect at Mumbai-based IMK Architects. This myopic approach has resulted in the creation of what Kadri calls vertical slums: “matchboxes in the sky where occupant discomfort and health issues are rife.”

“Empathy for the user, for the materials used, for the technology that forms this layer of experience between the universe and the contained space, is the tool for a designer for selective appropriation of that which is available and that which is possible,” says Dhruv Bhasker, who runs his design practice Samangal in Auroville. “The journey does not stop at the creation of this space; it begins with it.”

Also Read | Take a glance of Parineeti Chopra’s home to get some pristine views of the Arabian sea and more

Across the country, this approach seems to be gaining ground with architects and planners. Three of Delhi’s prominent neighbourhoods — Connaught Place, Chandni Chowk, and Karol Bagh — have been experimenting with the idea of creating no-vehicle zones during the daytime to promote pedestrianisation and enhance walkability. By freeing up space for the foot traveller and enabling them to commute and shop in decongested, pollution-free environments, these government-led initiatives signal a more empathetic and inclusive approach to urban design.

In Mumbai, Kadri is working on the redevelopment of slums and dilapidated housing societies using a novel framework grounded in empathy. Called ‘self-redevelopment,’ the process empowers slum dwellers or housing society inhabitants to take on the mantle of redevelopment themselves supported by the expertise of appropriate professionals. “The self-intent of the community accelerates the entire process and enables an inclusive and participatory design process. This directly and efficiently addresses the needs and concerns of the residents, fulfilling their expectations of better living conditions,” he says.

Also Read | Kangana Ranaut turns interior designer for sister Rangoli's new pad in Kullu (Manali)

While a bottom-up approach involving sustained community participation can mobilize action for bringing empathic design into mainstream practice, it requires strong support from policymakers to flourish. Bengaluru provides a shining example. The city’s citizens have joined forces with the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) to ramp up efforts towards lake conservation, leading to the revival of the Puttenahalli Lake, a water body that was almost entirely lost to human-induced degradation. Its success led to a spurt in similar initiatives involving multiple stakeholders and culminated in the creation of a citizen-led umbrella organization, Friends of Lakes, which works with environmentalists, ecologists, horticulturalists, and architects, among others to breathe new life into freshwater ecosystems.

“Empathic design can only emerge out of behavioural and cultural change,” says Ganju. “Social change and social justice are required to ensure that inclusive design and empathy can come to the forefront. It is a cycle; at the moment, we have a vicious cycle of degradation, and designers rank among the primary culprits. We can only reverse the cycle if we change our motivations.”

A broader shift in mindset is required to ensure that empathy jumpstarts a process of rebirth and renewal, creating possibilities for overcoming many of the significant challenges that we face today. Although much remains to be done, it is apparent that as opposed to an isolated approach where a few get to determine outcomes, a process where people come together to cooperate and collaborate can offer a sustainable model for effecting positive change in neighbourhoods, communities and by extension, cities.

The article has been published in an editorial partnership with Epistle Communications.

Also Read | Rehabilitation of an attic in a building dated 1906, in Lisbon